In the middle of the 18th century the world outside Russia was not known to the vast majority of Russians. St. Petersburg was founded by Peter The Great in 1703 at the end of the Great Northern War with Sweden on swampy land that was previously Swedish. In 20 odd years the city, as it was then, was virtually completed. Architects and technicians were brought in from all over Europe but labour, although plentiful and cheap, was totally unskilled so it was an incredible achievement.

As the century progressed so did travel and communication and mutterings began. The majority of the occupied territory in this vast country belonged to a number of immensely rich families all of whom owned huge numbers of serfs who worked the land and cared for every whim of their owners both on their numerous country estates and their palaces in St. Petersburg and Moscow where glittering balls and parties were held. One of the largest, the Sheremetevs, for instance owned 800,000 hectares and around a million serfs. Other families like the Goncharovs, Saltykovs, Orlovs and Tolstoys were proportionately similar. A little lower down the scale was the Volkonsky family descended from a 14th century prince who, after a glorious military career against the Mongol hordes, was awarded a large slice of land on the Volkona river south of Moscow.

Among the characters featuring strongly in the story of the Decembrist Uprising is a member of this family, Prince Sergei Volkonsky born in 1788. As a young man he, along with many others of his rich and aristocratic friends, had close connections with the Romanov Royal Family. His uncle was a close friend of Czar Alexander I and his brother, Nikita, was married to a lady who was a maid of honour in the Czar’s court and also his mistress. As a boy Sergei was a playmate of the future Czar Nicholas I who was to exile him to Siberia for life many years later. The Volkonsky’s St. Petersburg home was a substantial mansion on the Moika river where the poet Alexander Pushkin, also to play a part in the Decembrist saga, rented a suite of rooms. Two others to play prominent roles, but with significant differences were Prince Sergei Trubetskoy and Nikita Muraviev, the latter having eased himself into court favour. Curiously the language spoken in everyday conversation among the aristocratic and educated classes at that time was French. They only spoke Russian to their servants and many could hardly speak their own language at all.

Following his education at a prominent school, Abbot Nicola’s, attended by many of the rich and famous, Prince Sergei graduated from the Corps des Pages into the Guards. Wounded at the battle of Eylau in 1808, he was transferred to the Imperial staff in St. Petersburg and became a favourite of the Czar but, a year later, returned to the field of battle rising, at the age of 24, to the rank of Major General. He fought in over 50 battles including Borodino in 1812 and it was during this campaign that he became one of those increasingly disenchanted with the old fashioned Russian way of life. It was the first time that he and other officers like him had lived and fought with ‘ordinary’ people, serfs most of them. They went through the horrors of war and battles together, people dying all round them under the most appalling conditions, unparalleled scenes of bravery, pain and suffering and, perhaps as significant as anything else, comradeship. When it was all over small groups of them started to get together in secret to plan for the future. The groups started to amalgamate and eventually merged into two main sections – one centred in St. Petersburg under Nikita Muraviev and the other in Ukraine led by another Sergei, Muraviev-Apostol, a cousin of Nikita and Colonel Pavel Pestel, from a Siberian family, an idealist who, like Volkonsky, had fought with distinction at Borodino. He was also a romantic who had travelled through Europe, was a friend of Pushkin’s and a firebrand of ideas.

His plan was a military coup against the Czar whereas the St. Petersburg clan favoured a more diplomatic approach to establish a constitutional monarchy. Volkonsky’s position strategically was between the two groups having been appointed commander of the Azov regiment in Ukraine in 1815, the year of Waterloo, but was closely allied to the St.Petersburg section as well.

It has to be remembered that all meetings between the different factions were held in the strictest secrecy. Pushkin, for example, was not considered reliable or trustworthy enough to be a fully fledged member although a close friend of people in both camps unlike another poet, Kondrati Ryleev, a real fighter for reform and justice and who was a leading light in the St. Petersburg section.

1825 was a momentous year. Prince Sergei had met and fallen in love with the 18 year old  Maria Raevsky, daughter of General Nikolai Raevsky, Russia’s most popular military hero and friend and confidant of the Czar. The Raevskys came from a noble Scandinavian and Polish line gradually moving eastwards, the future general being born in St. Petersburg in September 1771. Nikolai’s father was himself a distinguished soldier and commanded a top line regiment but was killed in action during the Russo–Turkish War of 1768/74, months before Nikolai was born. Soon his widow, Nikolai’s mother, a niece of Potemkin, met and later married an immensely rich Ukrainian named Lev Davydov, the possessor of an enormous estate near Kiev. Nikolai had a military education and it was inevitable that he should enter the army. He had a most distinguished career taking part in all the wars fought by Russia from the second Russo-Turkish War of 1787/92, with Persia in 1796 and the Napoleonic Wars. He married a substantial heiress who came with a dowry of an estate and 6,000 serfs so with that and his estate inherited from his stepfather, the Raevskys were not exactly on the poverty line. They had six children including Nikolai’s favourite, Maria and, particularly in later life, Nikolai rejected any thoughts other than that Russia should remain under an absolute autocratic monarchy.

Maria Raevsky, daughter of General Nikolai Raevsky, Russia’s most popular military hero and friend and confidant of the Czar. The Raevskys came from a noble Scandinavian and Polish line gradually moving eastwards, the future general being born in St. Petersburg in September 1771. Nikolai’s father was himself a distinguished soldier and commanded a top line regiment but was killed in action during the Russo–Turkish War of 1768/74, months before Nikolai was born. Soon his widow, Nikolai’s mother, a niece of Potemkin, met and later married an immensely rich Ukrainian named Lev Davydov, the possessor of an enormous estate near Kiev. Nikolai had a military education and it was inevitable that he should enter the army. He had a most distinguished career taking part in all the wars fought by Russia from the second Russo-Turkish War of 1787/92, with Persia in 1796 and the Napoleonic Wars. He married a substantial heiress who came with a dowry of an estate and 6,000 serfs so with that and his estate inherited from his stepfather, the Raevskys were not exactly on the poverty line. They had six children including Nikolai’s favourite, Maria and, particularly in later life, Nikolai rejected any thoughts other than that Russia should remain under an absolute autocratic monarchy.

Prince Sergei Volkonsky and Maria Raevsky were married at the Church of St Andrew in Kiev on 12th January 1825. Maria’s father had mixed feelings; on the one hand, Sergei was a ‘catch’ – very rich and from a noble and aristocratic family; on the other hand, rumours were circulating about his friendship with the likes of Pestel. Sergei was also 17 years older than his wife. There was no doubt that he was deeply in love with her; she, although high spirited and adventurous had led a protected life and was naïve and bowled over by this hugely attractive and worldly Prince.

Prince Sergei Volkonsky and Maria Raevsky were married at the Church of St Andrew in Kiev on 12th January 1825. Maria’s father had mixed feelings; on the one hand, Sergei was a ‘catch’ – very rich and from a noble and aristocratic family; on the other hand, rumours were circulating about his friendship with the likes of Pestel. Sergei was also 17 years older than his wife. There was no doubt that he was deeply in love with her; she, although high spirited and adventurous had led a protected life and was naïve and bowled over by this hugely attractive and worldly Prince.

Following their marriage, Sergei returned to his military duties and, without mentioning a word to his new bride, continued his double life in the ‘Secret Society’. In fact during the first year of their married life, Sergei and Maria spent only about three months together but by mid May she was pregnant.

She spent some time in the Volkonsky Palace on the Moika canal in St. Petersburg which she found damp, depressing and austere. Masses of cold rooms with severe looking portraits of generations of Volkonskys staring down disapprovingly. The Palace was presided over in matriarchal fashion by Sergei’s mother, Alexandra, who was just a moving edition of another family portrait. Impervious to the cold, she was a princess in her own right from another prominent aristocratic family, the Repnins. As First Lady of the  Bedchamber to the Empress Elisabeth Alexeievna who, as Louise of Baden, married the future Alexander I (grandson of Catherine the Great) at the age of 14 when her husband was only 15, she considered herself closer than anyone to the Crown and certainly did not welcome the intrusion of her son’s young bride. Sergei’s father, on the other hand, was a delightful eccentric who lived far away in another Volkonsky Palace in the Urals in his capacity as Governor of Orenburg. Maria only met him once and he died before she and Sergei were married.

Bedchamber to the Empress Elisabeth Alexeievna who, as Louise of Baden, married the future Alexander I (grandson of Catherine the Great) at the age of 14 when her husband was only 15, she considered herself closer than anyone to the Crown and certainly did not welcome the intrusion of her son’s young bride. Sergei’s father, on the other hand, was a delightful eccentric who lived far away in another Volkonsky Palace in the Urals in his capacity as Governor of Orenburg. Maria only met him once and he died before she and Sergei were married.

The event that really threw both factions of the Secret Society off their stride was the sudden death of Czar Alexander I on 19th November aged only 47. The conspirators were finalising their plans but were simply not ready. The situation was made worse for them owing to a constitutional hiatus. Alexander had no children so his successor was his younger brother Grand Duke Constantine. However Constantine was very happily ensconced in Poland as Viceroy and C in C of the Polish army. He had no wish to return to the troubles and uncertainties that he foresaw in Russia and had, several years previously, renounced his succession to the throne – a fact that Alexander had not made known.

All hell broke loose on several fronts: constitutionally, Alexander’s youngest brother, Nicholas was next in line for the throne but he was unwilling to accept; mounted messengers dashed between St. Petersburg, Moscow and Warsaw from where Constantine reiterated his renunciation of the throne and refused to budge while Russia, and the outside world for that matter, watched and waited. In London the Times reported “The Russian Empire has two self denying Emperors and no active ruler”.

All hell broke loose on several fronts: constitutionally, Alexander’s youngest brother, Nicholas was next in line for the throne but he was unwilling to accept; mounted messengers dashed between St. Petersburg, Moscow and Warsaw from where Constantine reiterated his renunciation of the throne and refused to budge while Russia, and the outside world for that matter, watched and waited. In London the Times reported “The Russian Empire has two self denying Emperors and no active ruler”.

The Decembrists, as they were later to be named, were equally in chaos. Rumours had been circulating for a while but the leaders were planning an insurrection using the army for the late summer of 1826; following the death of the Czar, however, Pestel wanted to act immediately: Constantine was favoured by the army as being more reformist inclined but Nicholas was known to be a hard liner and an autocrat. On the 12th December, Nicholas finally agreed to become Czar of all the Russias and on 14th December the soldiers in all garrisons in St.Petersburg were instructed to swear an oath of allegiance to the new Czar. Pestel and the Decembrist leaders had hoped for 20,000  mutinous troops to enter Senate Square, dominated by the giant statue of the mounted Peter The Great, to demand for ‘Constantine and a Constitution’, but in the event, on December 26th and with many of their leaders absent for various reasons only 3,000 turned up. Pestel had actually been arrested on the previous day having been betrayed by a Captain Maiboroda from his own regiment, Trubetskoy changed his mind at the last moment and swore the oath to Nicholas and Volkonsky was still on his way from Ukraine. For hours the troops milled around the square in freezing temperatures waiting for instructions until Nicholas seized the initiative. First he ordered Count Mikail Miloradovich, a popular military hero, to go into the square and talk to the mutineers but he was shot and fatally wounded by Pytr Kakhovski, a fanatical hothead. That was the catalyst; Nicholas, who was in the square, then ordered the loyal troops who had surrounded the square to open fire on the mutineers. It was all over in a flash. Some 60 died on the square and rest fled.

mutinous troops to enter Senate Square, dominated by the giant statue of the mounted Peter The Great, to demand for ‘Constantine and a Constitution’, but in the event, on December 26th and with many of their leaders absent for various reasons only 3,000 turned up. Pestel had actually been arrested on the previous day having been betrayed by a Captain Maiboroda from his own regiment, Trubetskoy changed his mind at the last moment and swore the oath to Nicholas and Volkonsky was still on his way from Ukraine. For hours the troops milled around the square in freezing temperatures waiting for instructions until Nicholas seized the initiative. First he ordered Count Mikail Miloradovich, a popular military hero, to go into the square and talk to the mutineers but he was shot and fatally wounded by Pytr Kakhovski, a fanatical hothead. That was the catalyst; Nicholas, who was in the square, then ordered the loyal troops who had surrounded the square to open fire on the mutineers. It was all over in a flash. Some 60 died on the square and rest fled.

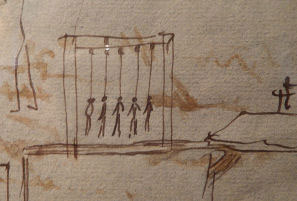

The rounding up of the Decembrist leaders began and it didn’t take too long. Nicholas was ruthless in his determination to stamp out the Uprising before any regrouping could take place. Volkonsky was arrested early in January and all the ringleaders and many others under suspicion were incarcerated in the Peter and Paul Fortress, a forbidding edifice on the opposite bank of the river Neva and in full view of the Winter Palace. Nicholas himself interviewed some of the ringleaders including Volkonsky and Trubetskoy with differing results. While Volkonsky stood up for his motives and loyalties, Trubetskoy broke down  weeping and begging for mercy. He got none. A total of 579 people were arrested and stood trial; most were acquitted or given minor sentences, and of the 125 major ‘offenders’ 5 were sentenced to death by hanging and the remaining 120 were exiled to Siberia for varying terms of hard labour from life (which meant ‘life’) to 10 years. When the sentences were announced guards ripped all decorations and insignias of rank from the uniforms of the prisoners and their swords were ceremoniously broken in two in front of them. Not only that – they were stripped of all assets, estates, rank and even name; they became just numbers and ‘non persons’. The five who were hanged were Pestel, the poet Ryleev, the killer of Miloradovich, Kakhovski, Muraviev-Apostol and a young 21 year old called Mikail Bestuzhev-Ryumin, a very active member of the southern section. The hanging did not, however, go according to plan. At that time in Russia there was no death penalty and

weeping and begging for mercy. He got none. A total of 579 people were arrested and stood trial; most were acquitted or given minor sentences, and of the 125 major ‘offenders’ 5 were sentenced to death by hanging and the remaining 120 were exiled to Siberia for varying terms of hard labour from life (which meant ‘life’) to 10 years. When the sentences were announced guards ripped all decorations and insignias of rank from the uniforms of the prisoners and their swords were ceremoniously broken in two in front of them. Not only that – they were stripped of all assets, estates, rank and even name; they became just numbers and ‘non persons’. The five who were hanged were Pestel, the poet Ryleev, the killer of Miloradovich, Kakhovski, Muraviev-Apostol and a young 21 year old called Mikail Bestuzhev-Ryumin, a very active member of the southern section. The hanging did not, however, go according to plan. At that time in Russia there was no death penalty and  therefore no hangman. One had to be imported for the job but evidently he was out of practise because he botched it for three out of the five. Among them was Muraviev-Apostol who exclaimed from the bottom of the pit: “ You see, in Russia they can’t even hang people properly”. There is a time honoured unwritten law that anyone surviving the hangman’s noose goes free but Nicholas was having none of that and ordered them to be strung up again. It must have been touch and go for Volkonsky and it has been said that his mother, as First Lady of the Bedchamber to the, now, dowager Empress, might have put in a word to Nicholas to spare him. As it was, he was in the first group of 8 of the most serious offenders to be dispatched to Siberia. His wife, Maria, gave birth to her son on 2nd January 1826 at the Raevsky estate in Ukraine but had no idea of her husband’s arrest or trial until several weeks later, the news of which was kept from her by her father. She was eventually told by Sergei’s brother, Prince Repnin and determined immediately that she would follow her husband into exile which caused consternation with her family, most of all with her father but her mind was made up.

therefore no hangman. One had to be imported for the job but evidently he was out of practise because he botched it for three out of the five. Among them was Muraviev-Apostol who exclaimed from the bottom of the pit: “ You see, in Russia they can’t even hang people properly”. There is a time honoured unwritten law that anyone surviving the hangman’s noose goes free but Nicholas was having none of that and ordered them to be strung up again. It must have been touch and go for Volkonsky and it has been said that his mother, as First Lady of the Bedchamber to the, now, dowager Empress, might have put in a word to Nicholas to spare him. As it was, he was in the first group of 8 of the most serious offenders to be dispatched to Siberia. His wife, Maria, gave birth to her son on 2nd January 1826 at the Raevsky estate in Ukraine but had no idea of her husband’s arrest or trial until several weeks later, the news of which was kept from her by her father. She was eventually told by Sergei’s brother, Prince Repnin and determined immediately that she would follow her husband into exile which caused consternation with her family, most of all with her father but her mind was made up.

As soon as she was able she travelled up to St. Petersburg and had a brief meeting with her husband in the Peter and Paul Fortress. But there were other problems: with Sergei’s assets having been confiscated and her father unwilling to help, Maria was short of money. She also had to obtain permission from the Czar to follow her husband which was not readily given. In fact it was several months before, very unwillingly, he granted permission. She did have one ally: Princess Katyusha Trubetskoy, wife of Prince Sergei Trubetskoy, who had broken down in front of the Czar, was also determined to follow her husband so they had a goal in common which was helpful in St. Petersburg and stood them in good stead at the other end of their journey later.

Maria had pawned her jewellery to raise money to pay for her journey and on Christmas Eve 1826 left St. Petersburg on the first leg of her epic 4,000 mile journey leaving her young son in the care of her family. During the last few days before leaving, many of her friends and family came to the Volkonsky Palace on the Moika canal to say good bye and on her very last day and after a tearful goodbye from her father, she spent most of it with Prince Peter Volkonsky, her brother-in-law married to Sergei’s sister Sophia. It was a sad and mournful occasion.

The story and saga of the Decembrist Uprising was the inspiration for a recent journey to St Petersburg and Siberia. In the former we wanted to walk where the Decembrists had trod and to see or at least imagine at first hand what they would have seen. We went, for example, to Tsarskoye Selo, the ‘village’ about 20 miles out of St. Petersburg, founded in 1710 and consisting in the main of a series of palaces and mansions to be occupied by or with the consent of the Royal Family.  The dominant buildings are the Catherine and Alexander Palaces and Parks spread over about 3,500 acres. The largest and most magnificent is the Catherine Palace named after Empress Catherine I (1684-1727) but it was really Catherine the Great who transformed it into the quite amazing structure that it is today, having been painstakingly and brilliantly restored after suffering extensive damage in WW2. Catherine brought in architects from all over Europe but one who stayed with her more than most and made Tsarskoye Selo his home was a British architect, Charles Cameron. The Alexander Palace, smaller and more intimate was built from 1792 to 1796. Among other prominent Tsarskoye Selo build

The dominant buildings are the Catherine and Alexander Palaces and Parks spread over about 3,500 acres. The largest and most magnificent is the Catherine Palace named after Empress Catherine I (1684-1727) but it was really Catherine the Great who transformed it into the quite amazing structure that it is today, having been painstakingly and brilliantly restored after suffering extensive damage in WW2. Catherine brought in architects from all over Europe but one who stayed with her more than most and made Tsarskoye Selo his home was a British architect, Charles Cameron. The Alexander Palace, smaller and more intimate was built from 1792 to 1796. Among other prominent Tsarskoye Selo build ings is the Lyceum where Alexander Pushkin studied for some years from 1811. A statue of the great poet has been erected in front of the building.

ings is the Lyceum where Alexander Pushkin studied for some years from 1811. A statue of the great poet has been erected in front of the building.

The Peter and Paul Fortress, the equivalent of the Tower of London but not quite of Alcatraz, was built by Peter the Great to protect the building of St Petersburg against a possible counter attack by the Swedes on whose land it was until Peter annexed it. It lies on an island nearly opposite the Winter Palace and Hermitage Museum. In the centre of the complex is the St. Peter and St. Paul Cathedral with the world’s highest Orthodox bell tower. The inmates of the prison have included such varied people as the anarchist Peter Kropotkin, Fyodor Dostoevsky and Leon Trotsky but it was the Decembrists that interested us most. The cells were actually quite large but during their incarceration, the water level in the Neva river was very high following a long period of heavy rain so that the walls were constantly dripping with water and conditions were not only cold but very damp. The prisoners were not allowed to see or converse with each other and were led into the small exercise yard one at a time over any 24 hour period.

It was on a slippery slope in front of the fortress, lit by a bonfire, that the sentences were announced and the medals, decorations and insignias were ripped off the prisoners as described earlier and thrown into the bonfire. Back on the other side of the Neva and only a few blocks to the left of the Hermitage on the river bank is Senate Square with its huge statue of a mounted Peter the Great and the scene of the massacre of the Decembrist rebel troops. At the time of our visit there were not too many people in the square and it was possible to soak in the atmosphere and imagine what had happened that cold December day 189 years ago.

No visit to St Petersburg is complete without a visit to the Hermitage – arguably the most famous museum in the world. The enormity of it all is in itself almost overpowering. The Winter Palace forms only apart of the whole museum. The entrance is reached by walking across a huge open square flanked by semi circular colonnades on both sides of the main gate – where, incidentally, the gentleman selling Russian fur hats did a roaring trade with us – the huge marble staircase to the first floor lit high above by enormous chandeliers was just a forerunner of what was to come.  The throne room, large enough to play a proper game of cricket, with a beautiful mosaic wooden floor, huge marble pillars and chandeliers, amazing painted ceiling and more gilt than ever seen; such opulence but produced in the highest design and decorative taste by the world’s foremost artists of the time just left one standing and staring with amazement. And so it went on, room by room full of priceless exhibits – one room with 35 Rembrandts, the whole Walpole collection, a fabulous Michael Angelo statue of a crouching boy, 12 rooms of Impressionists – van Gogh, Matisse, Monet, Gauguin, Cezanne – you name it, they are there. After a whole morning, just about all one can take at a time, we probably didn’t see half of the whole and even that moving on fairly swiftly.

The throne room, large enough to play a proper game of cricket, with a beautiful mosaic wooden floor, huge marble pillars and chandeliers, amazing painted ceiling and more gilt than ever seen; such opulence but produced in the highest design and decorative taste by the world’s foremost artists of the time just left one standing and staring with amazement. And so it went on, room by room full of priceless exhibits – one room with 35 Rembrandts, the whole Walpole collection, a fabulous Michael Angelo statue of a crouching boy, 12 rooms of Impressionists – van Gogh, Matisse, Monet, Gauguin, Cezanne – you name it, they are there. After a whole morning, just about all one can take at a time, we probably didn’t see half of the whole and even that moving on fairly swiftly.

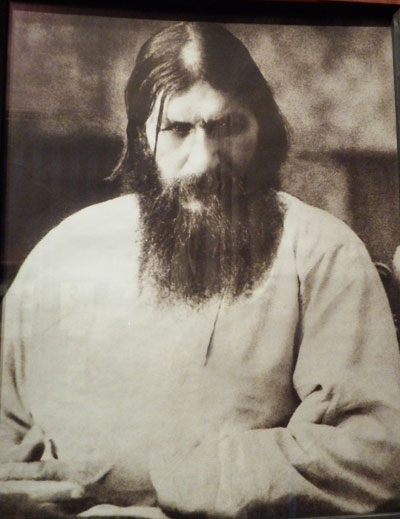

The old Volkonsky mansion is not open to the public but we drove past it and so could see where Prince Sergei lived and how it must have seemed to Maria when she was first married and also when she came to St Petersburg after her husband’s arrest and trial.  We did, however, go to the Usapov Palace, opulent and ornate, complete with its own fabulously designed private 200 seat theatre, to see where a scene in another turbulent episode in Russian history took place – the murder of Rasputin on the night of December 16/17th 1916 and also visited the Church of the Spilt Blood built on the very spot of the assassination of Czar Alexander II, the successor of Nicholas I, on 13th March 1881.

We did, however, go to the Usapov Palace, opulent and ornate, complete with its own fabulously designed private 200 seat theatre, to see where a scene in another turbulent episode in Russian history took place – the murder of Rasputin on the night of December 16/17th 1916 and also visited the Church of the Spilt Blood built on the very spot of the assassination of Czar Alexander II, the successor of Nicholas I, on 13th March 1881.

And so to Siberia. Maria Volkonsky’s journey took her first to Moscow where she arrived on the 6th day after leaving St.Petersburg and where she stayed for a few days with her sister-in-law Princess Zenaida Volkonsky, who was married to Sergei’s eldest brother, Nikita, at the family palace (now the British Embassy). Again it was a distressing and poignant scene. On the night before her departure and knowing Maria’s passion for music, Zenaida gave an intimate party for her with the most talented musicians in Moscow. Among those present was Alexander Pushkin, Maria’s great friend. Pushkin was probably in love with her and held her hand never leaving her side all evening. His lines in Eugene Onegin were inspired by his memory of Maria laughing and swimming in the sea in the Crimea:

How I envied the waves –

Those rushing tides in tumult tumbling

To fall about her feet like slaves!

I longed to join the waves in pressing

Upon those feet these lips …. caressing.

The speed with which she covered the often bleak and always snow covered land between Moscow and Irkutsk was incredible and was evidence of her determination to see her husband again.

Hardly pausing except to change horses every 14 miles or so, we pick up her story again as she arrived at the Moscow gate across the Angara river, in Irkutsk 23 days after leaving Moscow.

Irkutsk in those days was a forgotten outpost of about 15,000 inhabitants and most of the income was derived from trading in Oriental goods and the collection of taxes on furs. Hardly a position an ambitious young diplomat would seek as Governor and so it proved with General Friedrich Zeidler, German born and looking forward to retirement. His instructions from the Czar were to do everything possible to prevent Maria going any further. He failed, so tersely produced a document which she was forced to sign before she was allowed to go any further. In it she:

Renounces all her rights and becomes the wife of a State Criminal without any form of protection

Any further children born to her become serfs and the property of the State

She will not be allowed any valuables

She will not be allowed any servants

She will never be allowed to return to western Russia even on the death of her husband.

Even then, having signed the document, Ziedler took his time and Maria was subject to a rigorous customs inspection and treated in the way of a non person. Cleverly she and Zenaida in Moscow had sewn all her money in the hem and sleeves of her travelling clothes. What she did not know, at that stage, was that Katyusha Trabetskoy, wife of Prince Trabetskoy had only just left Irkutsk and had been subjected to the same indignities as Maria. Although she had left St. Petersburg a good month before Maria, her journey had taken her much longer. The one pleasant surprise that Maria discovered when unpacking her goods in Irkutsk was a small clavichord that Zenaida Volkonsky had given her and cleverly concealed when organising her departure from Moscow.

Thirty odd miles east of Irkutsk lies Lake Baikal, the next obstacle. Lake Baikal is 400 miles long, the deepest point is 5,300 feet, it is over 20 million years old and holds 20% of the world’s fresh water supply plus an abundance of a huge variety of fish. In the winter the lake freezes to a thickness of 4 to over 6 feet and where Maria crossed on her sleigh drawn by 3 horses the distance is 26 miles. We made the same crossing in the same manner; the first time, so we were told, that this had been done for 30 years. A never to be forgotten experience under a brilliantly clear sky but with temperatures of minus 20 degrees and under. The ice was not just smooth; the wind had created snow drifts and ice hummocks – frozen waves – with some ice mounds and shards over a yard high. In the centre of the lake looking across the wide expanse of shimmering white snow and ice, one could just pick out the mountains rising out of a haze on both shores. In places the ice was so clear that one could see a vivid reflection of the sleigh in the ice. For those worried about the world’s seal population, take heart. More than 100,000 live in Lake Baikal and, when it freezes, each seal keeps 14 separate air holes open.

We had started the crossing close to the small lakeside town of Listvyanka which had a pleasant almost alpine feel about it; on the other, eastern, shore we landed close to a village called Tankhoy to a very different and more backward scene. We drove for long distances through forests of mainly silver birch and pine, badly in need of thinning, before turning inland following the valley of the Selonga river, through the small town of Selinginsk where Maria had spent a night with a family of Polish immigrants from the days of Empress Catherine and where we stopped briefly to visit a working Swyato-Troitskiv monastery founded in 1670; Maria Volkonsky would definitely have stopped here on her journey. Lake Baikal forms an unofficial kind of demarcation line to the east of the lake and particularly in the country and rural area, there are many more Buryat people. The Buryats are a large Mongolian sect with distinctive high cheek bones; traditionally they are nomadic, independent herders of cattle, sheep and horses. Many are Buddhists with sharman traits but, more recently many have converted to Orthodox Christianity. Much of their background is shrouded in mystery which makes it all the more intriguing but the area in which we find ourselves at the moment on our journey, close to Ulan-Ude, has the largest conflux of Buryats outside Mongolia, the border of which is only 150 miles away.

Ulan – Ude, where we spent a night, is a thriving, attractive city founded in1775 as a stopping point for tea caravans trading between China and Russia; the city now combines very much the new and the old with a population of 400,000 about 30% of them being Buryats. Among the new is the recently modernised and refurbished to a high standard Opera House which we managed to get inside and have a look at while setting rehearsals were in progress for a new production. In the square opposite the Opera House stands the  world’s largest statue of the head of Lenin, 24 feet high and commissioned in 1970 to mark his 100th birthday. All rather different to when Maria passed this way but the old quarter, where she would have stayed has been well preserved.

world’s largest statue of the head of Lenin, 24 feet high and commissioned in 1970 to mark his 100th birthday. All rather different to when Maria passed this way but the old quarter, where she would have stayed has been well preserved.

Princess Maria’s ultimate destination was Nerchinsk and her journey was the same as taken by Prince Sergei and his fellow convicted state criminals nearly a year previously. From Ulan–Ude she still had another 500 miles to cover and her first stop after leaving Ulan–Ude would have been the village of Tarbagatai, an Old Believer village.

The Old Believers are traditional Orthodox Christians who broke away from the Russian church in 1666 when the Patriarch, Nikon, in Moscow decreed that the Church would reform to become closer with western style Christianity. The modifications were small and really quite trivial but the Old Believers, then and now, refuse to change.

We saw many such villages on our journey, distinctive by their houses brightly painted in strong colours, green, red, gold and blue. The inhabitants, too, mainly women it has to be said, beautifully dressed in full length multi-coloured dresses with heavy and ornate amber necklaces draped over their ample bosoms and flowery hats or bonnets of all colours. They welcomed us as visitors and invited us into their homes, plied us with food and vodka (a local ‘moonshine’ to be drunk with extreme care) and even sang and performed traditional songs and dances, one of them playing the accordion. Their strong wooden houses were as warm as toast inside heated by a central wood burning stove, wood being so plentiful and cheap. All the houses had yards stacked high with neatly sawn logs and in answer to a question to one lady about the current winter, elicited the reply (in Russian of course but translated) “Oh, quite good and not too cold, the temperature never went below minus 35 degrees!”

Maria reached Nerchinsk on the 10th day after leaving Irkutsk and a hell hole of a place it was, although the surrounding countryside was attractive enough. Hardly had she arrived when she heard her name being called and there, striding towards her was Katyusha Trebetskoy who had arrived a couple of days before her. Both their husbands were working in the same mine. Maria was so tired but so excited and on tenterhooks to see her husband but totally unprepared for what she was about to see. Having been subjected to a most unpleasant interview with the vile prison commandant, she was led with two guards to an underground dark dungeon; before her eyes became adjusted to the darkness all she could hear was the shuffling and clanging of chains and then the emaciated figure of her husband clad in filthy prison clothes appeared before her.

Maria was allowed to see her husband twice a week but only in the company of an officer and a guard. She and Katyusha found lodgings in one small room in a local house with fish skin in the window frame and not enough room to lie down flat so they slept on rugs on the floor propped up against the wall. They were in the depths of despair faced with living in a godforsaken place interminably with no one to turn to or help while their husbands remained incarcerated in chains even when digging 50 kilos of ore per day, their health deteriorating visibly. The eight in the original ‘intake’ in addition to Volkonsky and Trubetskoy and considered by Nicholas to be the most ‘guilty’ consisted of Prince Evgeni Obolensky, a classical scholar and academic, Nikita Muraviev, leader of the St. Petersburg faction, Vasya Davydov, General Raevsky’s half brother and therefore Maria’s uncle, the 2 Borisov brothers, Peter and Andrei and Yakubovich who was known to Maria and proved to be a valuable craftsman when needed later in the exile.

Later in the year of 1827 events took a different course emanating from a most unexpected source. Nicholas, who received regular reports on the Decembrists and would continue to be totally vindictive over their fate for the rest of his life, was worried about them on two counts: one, that they might consider escaping over the border to China, only a short distance away and, two, because of the appalling and unhealthy conditions in which they were living, if any of them should die the resulting publicity stirred up by the unwelcome presence of Maria and Katyusha plus the impending arrival of some of the other wives, would turn them into martyrs. He therefore decided that a purpose built prison should be constructed to house them and the man entrusted to find the site and oversee the whole operation was a retired 72 year old General called Stanislav Leparsky. Although Nicholas had no wish to make conditions easier or more pleasant for the Decembrists, the choice of Leparsky was a good one from their point of view; he was a tough disciplinarian but had a kindly, human side.

The site selected was just outside a small settlement called Chita close to where Genghis Khan once ruled. It was also the most eastern point in our journey with a 10 hour time difference with GMT; in other words at 7 a.m. UK time it is 5 p.m. in Chita. Looking down now on Chita from a nearby hilltop it is difficult to imagine a sleepy little village in 1827; set in a bowl surrounded by mountains it is now a huge railway junction with railway tracks thrusting out in all directions carrying mainly freight trains, some of them approaching half a mile long hauled by three monster electric engines. A smoggy haze hovering above the city slowly cleared into the brilliant blue sky like adjusting the focus of a camera.

The Decembrists were delighted to be moving there after the sheer hell of Nerchinsk, another reason for the move being that, apart from the Volkonsky group, other prisoners were placed in equally horrid camps in the area and it was considered by the authorities that it would be better to have all the Decembrist prisoners in one place. They were equally thrilled to be together again. The very beautiful Alexandrine Muraviev – Nikita’s wife – was already there and wrote enthusiastically about how lovely it all was. The move was made, the 8 prisoners, all by this stage in very poor health with Volkonsky the most debilitated, under a guard of 14 Cossacks. The journey took only two days under cold but sunny skies illuminating the autumnal colours of the forests. The wives travelled separately but Maria had managed to smuggle a couple of bottles of Madeira into their husbands’ prison clothing to help them during the journey.

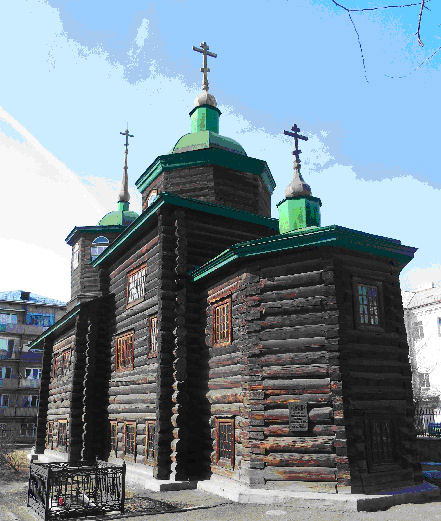

After Nerchinsk Chita seemed like Eldorado. The purpose built prison under the direction of the kindly Leparsky was light and airy and even had heating; most importantly, though, they were all together. Chita was on the east/west trading road from China to Irkutsk and all points west but it had a sort of micro climate and was described as the garden of Siberia. There wasn’t much there – about 600 people, a pretty old wooden church and not much else but the soil was good and crops of wheat, barley and vegetables grew in abundance. Prison conditions still only permitted two visits each week but now the prisoners were allowed, under company of a guard, to come to where their wives were living. The ladies had quickly managed to make friends with the locals and with their help and with good quality timber being plentiful and cheap, had built a little community of houses within sight of the prison so they could frequently catch sight of their loved ones inside the prison compound. The prisoners were still chained, however, and the sound of jingling chains became a familiar announcement of a visit. The work, too, was easier consisting in the summer months of digging ditches and trenches to improve irrigation and menial, heavy work in the local mills in the winter. Occasionally in the summer the wives were allowed to go to where the prisoners were working and almost a picnic atmosphere existed.

After Nerchinsk Chita seemed like Eldorado. The purpose built prison under the direction of the kindly Leparsky was light and airy and even had heating; most importantly, though, they were all together. Chita was on the east/west trading road from China to Irkutsk and all points west but it had a sort of micro climate and was described as the garden of Siberia. There wasn’t much there – about 600 people, a pretty old wooden church and not much else but the soil was good and crops of wheat, barley and vegetables grew in abundance. Prison conditions still only permitted two visits each week but now the prisoners were allowed, under company of a guard, to come to where their wives were living. The ladies had quickly managed to make friends with the locals and with their help and with good quality timber being plentiful and cheap, had built a little community of houses within sight of the prison so they could frequently catch sight of their loved ones inside the prison compound. The prisoners were still chained, however, and the sound of jingling chains became a familiar announcement of a visit. The work, too, was easier consisting in the summer months of digging ditches and trenches to improve irrigation and menial, heavy work in the local mills in the winter. Occasionally in the summer the wives were allowed to go to where the prisoners were working and almost a picnic atmosphere existed.

Being together and in better living conditions helped to inspire the men to become both imaginative and creative; they were, after all, intelligent and well educated. Prince Evgeni Obolensky, Pavel Mozgan and Anton Arbuzov designed and made clothes, Nikolai and Mikail Bestuzhev became cobblers, Nikita Muraviev lectured on military strategy with the aid of maps which he plotted himself, Volkonsky was an ardent and knowledgeable gardener; they were very lucky to have former Surgeon General Ferdinand Wolff among them whose medical skills were in constant demand by his co-prisoners and also by the ladies. There were musicians: Alexander Yushnevsky, for example was an excellent pianist, a string quartet was formed and gave recitals and Maria still had her clavichord.  From a pictorial record point of view, probably the most influential was Nikolai Bestuzhev who had trained at the Imperial Academy of Arts and whose original paintings and prints of many views and aspects of the Decembrist’s exile we saw during our journey.

From a pictorial record point of view, probably the most influential was Nikolai Bestuzhev who had trained at the Imperial Academy of Arts and whose original paintings and prints of many views and aspects of the Decembrist’s exile we saw during our journey.

In 1828 a double tragedy struck: Sergei and Maria’s two year old son died in St. Petersburg and later in the year Maria’s father, the old General Raevsky, also died. Both deaths hit Maria deeply: she had pangs of guilt about leaving her young son in the hands of his grandmother and the cold, damp palace in St. Petersburg and, despite everything, she was devoted to her father who had never really got over her departure to Siberia so much against his wishes. The whole Decembrist matter had caused an huge rift between the Volkonsky and Raevsky families.

In the autumn of 1829 Maria was delighted to be pregnant again but even this had a very sad outcome for, at the beginning of July 1830, she gave birth to a daughter who lived for only two days. The little wooden church in Chita saw much happiness since the arrival of the Decembrists: several were married there including Ivan Annenkov, a very rich, fun loving and social Guards Officer who had been having a rip roaring affair in St. Petersburg with a socially unacceptable vivacious and attractive French lady, a dressmaker called Pauline Gueble. Marriage was out of the question even though Pauline had a child by Ivan.

After the Uprising and Ivan’s exile, Pauline, overcoming almost more difficulties than Maria including with Ivan’s mother, the formidable and fabulously rich widowed Mme. Annenkov, reached Chita and they were married in the church two days later with General Leparski as best man. To conform with the Orthodox religion, Annenkov was permitted to have his chains removed for the service only to have them replaced immediately afterwards. Despite pleas to Leparski for a little leniency, he refused to allow Annenkov any ‘time off’ after the service and so consummation of the wedding had to wait until his allotted house visit two days later.

But the church saw sadness too: the tomb of little Sonyushka, Maria and Sergei’s daughter lies just outside. Nowadays the church has been very well renovated and is a truly excellent Decembrist Museum where we spent a whole afternoon. It is interesting that although in St. Petersburg – and to a lesser extend in Moscow where we spent a couple of days on the return leg of our journey – there are lots of monuments and exhibits of the Decembrists, the Uprising is not considered now of such huge importance whereas in Siberia from Irkutsk and particularly on the eastern side of Lake Baikal, the Decembrist exiles are revered to a high degree both by monuments and by the populace. Some of the older people to whom we spoke, via interpreters, had grandparents who had strong memories of the Decembrists.

Throughout the year rumours had been circulating about another prison move on the orders of the Czar and in July, General Leparski confirmed that the Decembrists would move 450 miles to a new, in every sense, prison at Petrovsky Zavod. The news did not go down well and they were fearful of the journey and what awaited them at the other end. They had been in Chita for three years.

DECEMBRISTS JOURNEY FROM CHITA TO PETROVSKY ZAVOD. – translated from the original Russian

They left Chita on 7th August 1830 in two groups, one under the command of General Laparsky and the other under his nephew Osip Adamovich, both groups accompanied by guards of mounted Cossacks.

A diary of one of the Decembrists survives with his account of the journey. He describes that “Crowds came. Everyone was crying, saying goodbye to us, wishing us well” and when crossing the Chita river, “ I admired the clever agility of the Buryats who ferried. Rain did not stop. Cold” and “Town ladies came to look at us” Later … “Commandant told us how to go through the city. Soldiers were told not to talk to us and to have a ferocious appearance. We roared laughing ahead, amused by the impossibility of implementing these smart orders”

August 8th. On entering Saentuevskaya met by “Crowds of local people, only stupid curiosity on their faces”.

Later, on August 21st “ Bored, snowed in night. Met Dalai (Buryat): nice guy, speaks Russian, understands everything. I gave him a comb as a souvenir………Buriat are very kind people. Kindness and meek are the main qualities of these people.”

August 24th In Hara-Shibir “Their ancestors were Polish immigrants but there is nothing Polish in the descendents”

August 25th “News about the French Revolution”. This was the July Revolution triggered by the death of Louis XVIII and the news was brought by Anna Rozen, wife of the Decembrist Baron Andrei Rozen, who had found out about the journey and had waited for three years to join her husband.

August 26th In village of Griadetskaya “Lovely open views, on the sides – Buryat camps. Herds, hay fields, huts look like Russian ones.”

August 28th “Watched shaman (a priest of a Siberian religion based on the influence of good and evil spirits). He is old and not as popular any more, that’s why all his tryings looked foolish. Taisha was visibly laughing at him to show us what she is thinking about. Nowadays shamans are being chased by llamas, therefore it is hard to find the good one.”

August 31st “Went to banya (Russian sauna) of merchant Losev. His son supplied us with meat”.

September 2nd. In Tinshri-Baldetskaya, “Weather constantly good. Went near mountain where one can see signs of alabaster and marble”

September 4th In Kurbinskaya “Went twice through pine woods. Nice river Uda ……. Met Scottish bible missionary …….. Storm during night, thunderstorm, rain….. Crossing Kurba river. The most difficult and tiring transition”

September 6th “Strong wind. Most yurtas (tents) were demolished during the night.”

Later, during the last few days of the journey “Fon-Vizin announced details of Karl X abdication (King Charles X of France). This revived everyone. Conversations, judgements”

On the day of arrival in Petrovsk Zabailkalsky: “ Everything sort of told us about coming closer to our graveyard, where our graves were already made for us ………… We looked at our future place of stay from the hill and were making jokes. While coming near, loads of people came out. Near the house of Alexandra Grigorievna all our ladies were standing near the fence. We entered our Bastille with good mood, ran into the embraces of our friends who we didn’t see for 48 days, ran to our prisons. I entered my room. Dark, damp, stuffy. The real coffin”

The journey had taken 49 days and covered approximately 450 miles. Another Decembrist, Baron Schteingel describes the journey as being quite calm with lunch being followed by a siesta even by most of the guards with the weather becoming hot by day but cold at night. He reports that one day they were visited by a Buryat chieftain who took on the two best Decembrist chess players and beat them both hollow.

______________________

The foreboding fears of the Decembrists about Petrovsky Zavod, or Petrovsk-Zabailkalsky as it is called now, were fully realised on arrival. Today it really is a pretty awful place: tired, unkempt, unattractive rectangular blocks of flats dotted hither and thither, roads and streets full of potholes and littered with rubbish with tufts of dirty grass poking through the melting snow and occasional splashes of modern Soviet type architecture plonked here and there. In the middle of virtually nowhere a hideous and ornate City Hall stands totally out of context with the surroundings.

During WW2 a large iron ore refinery was constructed here but apart from a lot of rusty old plant and buildings, there didn’t seem to be much going on at the time of our visit. Of course it didn’t look anything like this in 1831, the year the Decembrists arrived at their new prison, designed specifically to the orders of Nicholas I, roughly in the shape of a horseshoe with a red roof but no windows at all in the cells so no daylight.

The doors, of course, were padlocked shut. The prison is not there anymore but we know what it looked like thanks to Nikolai Bestuzhev’s drawings and paintings. On the plus side, some of the hard and fast rules were becoming less onerous: the chains and leg irons had been removed before leaving Chita and wives were now allowed inside the prison and could share a cell with their husbands.

Nevertheless Maria and the other wives got together with many of the prisoners and local inhabitants and built wooden houses for themselves. They normally went to their daytime houses to do their chores and correspondence before returning to their husbands cells to be locked in for the night. General Leparsky was still in charge and he gave his backing to a petition to the Czar by the prisoners to have windows let into the cells. After many months of waiting permission was reluctantly granted but only for 1 foot square windows 7 feet from the floor.

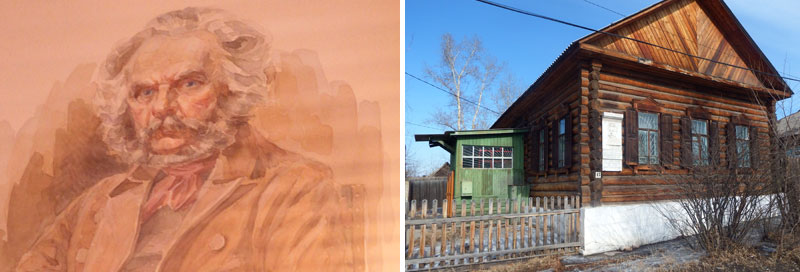

In 1832 Maria had a baby boy which she and Sergei called Mikhail or ‘Misha’ followed in 1834 by a daughter, Elena (Nelly). But all was not well: for some time Sergei Volkonsky, now in his early forties, was retreating more and more into himself. He was passionate about his gardening and growing vegetables to increase the food supply spending more and more time on his own and away, mentally, from his wife, friends and family.  He was probably displaying the thoughts and actions that made him a reactionary to his elevated and autocratic upbringing in the first place, hence his involvement in the secret society and the Uprising. There is little doubt that his wartime and battle experiences affected him to the extent that he felt he must do something to change the system of government. Now that it had failed he felt huge resentment and turned his attention to the only form of productivity that his circumstances permitted. He dressed in peasants clothes, let his beard grow long and straggly and was a changed person. Maria took a lover. Alessandro Poggio was, as the name suggests, of Italian extraction, his father, an Italian nobleman having come to Russia in the 1770s in circumstances clouded in mystery and romance. Poggio, by all accounts, was dashingly good looking and fun loving with an attractive personality and popular with all; his romantic outlook on life had drawn him to the Decembrist cause. He was also a lot younger than Sergei having been born in 1798 and he provided a shoulder for Maria to cry on and more. She started to spend more nights away from the prison and Alessandro was to be seen spending more and more in Maria’s house. Their affair was common knowledge in the prison but Sergei didn’t seem to mind and referred to Poggio as ‘his great friend’ The rumour, unconfirmed and never proved, was that he was the father of both Misha and Nelly.

He was probably displaying the thoughts and actions that made him a reactionary to his elevated and autocratic upbringing in the first place, hence his involvement in the secret society and the Uprising. There is little doubt that his wartime and battle experiences affected him to the extent that he felt he must do something to change the system of government. Now that it had failed he felt huge resentment and turned his attention to the only form of productivity that his circumstances permitted. He dressed in peasants clothes, let his beard grow long and straggly and was a changed person. Maria took a lover. Alessandro Poggio was, as the name suggests, of Italian extraction, his father, an Italian nobleman having come to Russia in the 1770s in circumstances clouded in mystery and romance. Poggio, by all accounts, was dashingly good looking and fun loving with an attractive personality and popular with all; his romantic outlook on life had drawn him to the Decembrist cause. He was also a lot younger than Sergei having been born in 1798 and he provided a shoulder for Maria to cry on and more. She started to spend more nights away from the prison and Alessandro was to be seen spending more and more in Maria’s house. Their affair was common knowledge in the prison but Sergei didn’t seem to mind and referred to Poggio as ‘his great friend’ The rumour, unconfirmed and never proved, was that he was the father of both Misha and Nelly.

There was an increasing number of babies born to Decembrist wives: the Annenkovs, Muravievs, Davydovs and particularly the Trubetskoys all bred a clutch so there was plenty of childrens’ playtime and also a need for them to be educated, something which Maria and many of the other wives took seriously and, with the help of Leparsky in obtaining books and learning tools, set up a school which could also be attended by local children.  They were greatly assisted in this project by one of the Decembrists, Ivan Gorbachevski, a big, solid man of high intellect, principles and a natural revolutionary against autocracy. After his release on completion of his sentence he stayed on in Petrovsky Zavod and continued to teach until his death in 1869. We went to the house where he lived and taught which is kept as a shrine to him.

They were greatly assisted in this project by one of the Decembrists, Ivan Gorbachevski, a big, solid man of high intellect, principles and a natural revolutionary against autocracy. After his release on completion of his sentence he stayed on in Petrovsky Zavod and continued to teach until his death in 1869. We went to the house where he lived and taught which is kept as a shrine to him.

He once published a vicious attack on Pushkin condemning his lifestyle which, he said, was why he could never have been trusted as a member of the Secret Society.

A huge sadness awaited them all at this time – particularly Nikita Muraviev. His stunningly beautiful and immensely popular wife, Alexandrine (Annie) caught a bad chill and died within a week despite all the best efforts of Dr Wolff to save her. She was only 28 years old. Her death caused enormous depression over all the Decembrist as she was loved so much by all. Her tomb, perched high in the cemetery at Petrovski Zavod to this day bears witness to this.

Another to make his mark was the philosopher Mikhail Lunin; very much a loner and a catholic, he was nevertheless always pleasant and good company when he had to be. He played the guitar and entered, at times, into the activities of the others. When the rules regarding prison life relaxed somewhat, Lunin used to climb a high and steep hill overlooking the prison and the town.

Close to the summit he had erected an enormous Cross as a memorial to the Decembrists and although his original one has long since decayed, another very strong wooden Cross stands in exactly the same place and it is here that Bestuzhev painted one of his best views of the prison. After his release Lunin was later re-arrested for publishing subversive material and ended his life in prison. In Petrovsky-Zabailkalsky there are more Decembrist monuments than in any town or city in Russia except St. Petersburg.

Although most of the Decembrists’ sentences included exile for life the periods of hard labour varied so gradually the prison population diminished as those released were sent to various settlements in Siberia to live out the remainder of their lives. The Volkonskys were among those sent to Urik, a small settlement, little more than a village only about 20 miles from Irkutsk; they were not permitted to live any nearer to Irkutsk. As ‘postings’ go this was a good one; many fared worse, trapped, more or less, in obscure Buriat villages east of Lake Baikal with no medical or educational facilities. How much this favourable posting was due to Sergei’s state of health is not known but he had chronic bad arthritis, bladder problems and had lost nearly all his teeth. He was even sent away from Petrovsky to some mineral baths for a couple of months from where he returned considerably improved.

Just before departing for good from Petrovsky–Zavod the news came through that Alexander Pushkin had been killed in a duel with Georges D’Anthes, a French Cavalry officer whom Pushkin had accused of having an affair with his wife, Natalia. Maria was devastated. Pushkin had been her golden hero since childhood. So it was with delight but also heavy hearts that in March 1837 Sergei and Maria with their two children, Misha and Nelly climbed onto a troika and left formal prison life for the last time, this time going west, across the still frozen Lake Baikal, alongside the Angara river, the only river to flow out of Lake Baikal, and on to this little village not that far from Irkutsk. In Urik they were greeted by Dr. Wolff and also by Nikita Muraviev and his daughter Nonushka. They quickly set to and within a month or so had selected their timber and built themselves a proper sized house overlooking the Angara river. Mikhail Lunin was also there and he, Nikita Muraviev and a mathematician called Peter Makhanov organised school classes for the children. Within a year Alessandro Poggio had joined the community from Petrovsky–Zavod but he brought with him the sad news that the kindly old General Leparsky, who had done so much to make life for the Decembrists less intolerable, had died. His tomb with a suitable monument lies just below Alexandrine Muraviev’s in the cemetery in Petrovsky–Zavod.

The settlement of Urik has seen far less change in the intervening years than any of the other places that we saw on our journey where the Decembrists had been forced to live. Even now it is just a collection of houses in a couple of streets, a shop or two and a church. On the express orders of the Czar each ‘freed’ Decembrist was allotted 42 acres on which he was expected to produce enough food for his family. It may sound quite a lot but with the ground being frozen solid for so much of the year it could not have been easy. Sergei Volkonsky’s health may have improved physically but mentally he was a mere shadow of the good looking, forward thinking army officer and conscientious aristocrat that he once was. He did, however, throw himself full time into his agricultural ‘patch’ and here he was much helped by his wife’s lover, Alessandro Poggio, who also had green fingers. In fact the two men remained good friends for the rest of their days.

The settlement of Urik has seen far less change in the intervening years than any of the other places that we saw on our journey where the Decembrists had been forced to live. Even now it is just a collection of houses in a couple of streets, a shop or two and a church. On the express orders of the Czar each ‘freed’ Decembrist was allotted 42 acres on which he was expected to produce enough food for his family. It may sound quite a lot but with the ground being frozen solid for so much of the year it could not have been easy. Sergei Volkonsky’s health may have improved physically but mentally he was a mere shadow of the good looking, forward thinking army officer and conscientious aristocrat that he once was. He did, however, throw himself full time into his agricultural ‘patch’ and here he was much helped by his wife’s lover, Alessandro Poggio, who also had green fingers. In fact the two men remained good friends for the rest of their days.

This kind of very strange life, being not prisoners but not free men either, continued for 8 years until in 1845 many were allowed to move into Irkutsk; The Trubetskoys were allowed and so was Maria but Sergei was not. The Trubetskoy built a substantial house and so did Maria but poor old Sergei was only allowed to make one visit per month .

Both houses are still standing today and are shown as museums to both families and to the Decembrist movement. We visited them both and in the Volkonsky house where the original Maria clavichord is still played, were treated to a short concert played and sung by local musicians.

Maria, and most of the other ladies threw themselves into projects like schools, building a theatre and enthusing the local people to take part in their own affairs, to read and learn about the rest of Russia and indeed the world outside Russia.

This, then, nearly draws to a close the saga of the Decembrist Uprising and what happened to the instigators. But not quite. Various events affecting the families took place during the Urik/Irkutsk years like when Nikita Muraviev died in Urik in 1843 but in February 1855 Czar Nicholas I died, a broken man, his dreams in tatters the final humiliation being the Russian defeat in the Crimean War which seems to have been an even bigger administrational disaster for the Russians as ours was for us, let alone the enormous and unnecessary loss of life on both sides.

Nicholas was succeeded by his son, Alexander, a much more humane and kind man who not only remembered but secretly sympathised with the Decembrists. He was crowned Emperor Alexander II in 1856 and declared an amnesty for all the Decembrists. Sergei and Maria’s son Misha sped immediately to Irkutsk to bring this joyous news to his father (Maria had been given permission to leave earlier). The old man was overcome with delight and it must have been a very touching moment between father and son. Within a week, together they started their journey back to Moscow where they were rapturously greeted by Maria and the rest of the family. Great scenes of celebration with parties and balls took place over the following weeks and Sergei seemed a transformed man: gone were the peasants’ clothes and straggly beard. He was smartly dressed, articulate and every inch the Grand Old Aristocrat again. But he never regretted his part in the Uprising and wrote towards the end of his life that he would have not changed anything which is a fitting epitaph to a man of principle in doing what he believed to have been right.

Nicholas was succeeded by his son, Alexander, a much more humane and kind man who not only remembered but secretly sympathised with the Decembrists. He was crowned Emperor Alexander II in 1856 and declared an amnesty for all the Decembrists. Sergei and Maria’s son Misha sped immediately to Irkutsk to bring this joyous news to his father (Maria had been given permission to leave earlier). The old man was overcome with delight and it must have been a very touching moment between father and son. Within a week, together they started their journey back to Moscow where they were rapturously greeted by Maria and the rest of the family. Great scenes of celebration with parties and balls took place over the following weeks and Sergei seemed a transformed man: gone were the peasants’ clothes and straggly beard. He was smartly dressed, articulate and every inch the Grand Old Aristocrat again. But he never regretted his part in the Uprising and wrote towards the end of his life that he would have not changed anything which is a fitting epitaph to a man of principle in doing what he believed to have been right.

Curiously Maria did not adapt back to life in Moscow and St. Petersburg as well as Sergei. She could not put out of her mind the 30 years of exile, of how she coped with it and the contribution she had made to the various communities where she had lived in Siberia. During her last few years in exile she had suffered intermittently with a kidney problem and after a relatively short time back in the west, this had manifested itself and she became very frail and ill. She died at Veronky, the Volkonsky estate in Ukraine, in August 1863. Sergei, by this time was failing himself and Maria’s death completely devastated him. Throughout all his married life and despite all his periods of eccentricity, he remained devoted to Maria and perhaps an example of this was the way he accepted Maria’s affair with Poggio in the knowledge that he could not, himself, provide her with all that she wanted or, for that matter, deserved. Although remaining mentally alert to the end, he, too, died at Veronky, aged 77 two years later in November 1865. Of their two children Misha rose to high rank in the Civil Service and married well and happily; Elena, after a first disastrous marriage which ended with the death of her husband, subsequently married Prince Kochubey with whom she remained blissfully happy. Czar Alexander II was assassinated in St Petersburg in March 1881.

After leaving St. Petersburg and during our journey following the Decembrist trail in Siberia, we stayed in some pretty varied accommodation: two quite reasonable hotels, two grotty hotels, one attractive, small chalet type hotel, a biosphere nature preserve and information centre hostel, a night on a trans Siberian train and a night in a Sanatorium which had some spare accommodation where we were well looked after, the only surprise being that some of the inmates who we saw on arrival were still alive the next morning.

So, what’s the answer to the question posed in the title of this piece?

First, why did it fail? It failed for two main reasons: the first one being the untimely death of Czar Alexander I and the succession of Nicholas. Next, with Alexander, the Decembrists stood a chance provided they could have mounted a united front, i.e. that the two factions of North, Muraviev, Volkonsky and Trubetskoy, and the South, Pestel and Muraviev-Apostol could have agreed tactics. Moreover they could have worked with Constantine too but they knew from their Court sources that he wouldn’t leave Poland. And they knew as well that they had no chance with Nicholas. Their only hope was to bring their whole operation forward by seven months with only a few weeks to complete their plans. As we have seen, it was a disaster.

Would success have changed the course of history? There are many imponderables but, given a fair wind, the probable answer is Yes. The writing was on the wall for Russia; agitation was gaining strength, increased travel, communication and depth of learning was on the up but she was faced with a blind, autocratic and despotic out of date ruler surrounded by sycophants. Had a reformed and modernised constitutional monarchy materialised there should have been no need for the Revolution of 1917, the likes of Lenin and more particularly Stalin would not have gained prominence and hundreds of thousands of lives would have been saved, not to mention the intolerable living standards and standards of living introduced and brought on by Communism.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.

In writing this piece I have drawn not just on my own research over a two year period but also from two most invaluable and brilliant books on the subject: The Princess of Siberia by Christine Sutherland and Natasha’s Dance: a Cultural History of Russia by Orlando Figes.

A huge debt of gratitude to my friend and agent, Alexei Nikiforov and his team at Absolute Siberia who made all the plans and arrangements in Siberia possible and to Olga Koshutskaya, our splendid guide in St. Petersburg

My grateful thanks also to Natalia Trudneva for providing essential translating documents written in Old Russian.

Last but by no means least my love and thanks to Della Burke and my lovely Cilla for all their help in checking the manuscript and fitting all the photographs in the proper places!

A.J. April 2014.

Photographs by Antony Johnson and Cilla Perry.

Antony Johnson

Coltleigh Farm, Mapperton, Beaminster Dorset DT8 3NR

Telephone: 01308 862630

Email: antony@fhtt.co.uk