Constable, Gainsborough, Turner: The Making of British Landscape

At the Royal Academy

8 December 2012 – 17 February 2013

Aside from its blockbuster, coffer-filling exhibitions, the RA often offers little stocking-filler exhibitions – usually small, low-budget, bijou shows, drawn from their own collection.

Now that the surprisingly successful Bronzes exhibition has finished and before they open their next big blockbuster, Manet’s Portraits (26 January – 14 April), they have a charming, if slightly academic, exhibition in the opulently gilded John Madekski Rooms and two adjacent rooms. All the works come from the RA’s own collection, though they have never been shown together and many are little known.

The exhibition explores the rise of a distinctive British school of landscape painting in the second half of the 18th century, modelled on 17th century French, Italian and Dutch masters, and the emergence of the aesthetic categories of the Beautiful, the Sublime and the Picturesque. The 18th century philosophers Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant sought to differentiate the concept of the Beautiful from that of the Sublime, the Beautiful evoking familiar experiences and thus promoting pleasurable feelings, whereas the Sublime stemming from the unfamiliar (towering mountains, jagged gorges and rushing torrents) and thus prompting feelings of awe, terror or mystical reverence. The Picturesque is situated ambiguously between the Beautiful and the Sublime.

The exhibition includes a large number of prints, but also some very fine watercolours, drawings and paintings.

From its inception in the 1760s, the RA chiefly promoted ‘history’ paintings (i.e. paintings based on biblical or mythological subjects) as the quintessence of artistic achievement. Landscape, like portraiture, was considered in Britain as elsewhere in Europe, a lesser genre, but it nonetheless flourished at the RA, nurtured by such Founder Members as Richard Wilson, Paul Sandby and of course Gainsborough.

You can rush through the first small room, which, uninspiringly, displays dull contemporary works in other media, which broadly fall under the category of landscape, from a text by Richard Long, RA, to a stone sculpture by John Maine, RA.

Room 2 concentrates on prints after paintings by Claude, Nicholas, Berchem, Poussin’s brother-in-law, Gaspar Dughuet, confusingly referred to as Poussin at that time. One is apt to forget that, until the opening of Dulwich Picture Gallery in 1815, there were no public galleries in Britain and, before the founding of the British Institution in 1805, there were no exhibitions of old master paintings, so art lovers and artists could only visit country houses or Christie’s auction rooms or of course venture to the Continent. We can therefore understand why Gainsborough wrote to the actor David Garrick with such excitement after seeing Rubens’ The Watering Place ‘in the flesh’ in the Duke of Montagu’s Dressing Room in 1768.

The lack of public exhibitions of great paintings explains the phenomenal success of prints in that period – today prints of old master paintings are considered of fairly academic interest.

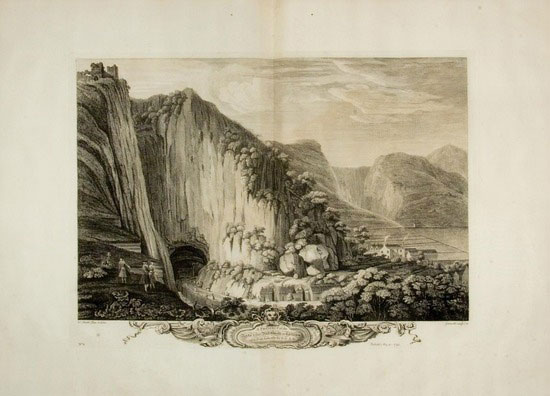

Room 3 honours the truculent and bibulous Welshman, Richard Wilson (often called ‘The English Claude’) and Thomas Smith of Derby as respectively founding father and unsung pioneer of British landscape painting. It also features those engravers most skilled at converting the ‘gold’ of 17th century Italian oil paintings into the ‘brass’ of lucrative engraving. For example, Wilson’s Destruction of Niobe and her Children became one of the most admired paintings of its time, but it was known mainly thanks to William Willett’s engraving. Most visitors will be unfamiliar with Thomas Smith of Derby (most of his works being in Derby and museums up north) but may well be won over by the elegant set of Eight of the most extraordinary Prospects in the Mountainous parts of Derbyshire and Staffordshire, which celebrate the new fascination with the rugged and frightening in actual places, on display in this room.

Thomas Smith of Derby

One of the other lovely prints in this room is of Wilson’s Bridge over the Taaffe in South Wales, showing the elegant, single-arched, 140-foot hump-back bridge, a minor architectural marvel, curiously sited amidst the desolate wilds of Wales.

Room 4 is the largest room, which displays some important paintings, including a Gainsborough Self Portrait (aged 60) – it is interesting to recall that, in his 40s, Gainsborough was already writing that he was tired of painting portraits and longed to simply paint landscapes ‘and enjoy the fag end of his life in quietness and ease’. This room also displays his prosaically titled Romantic Landscape (1783); Turner’s brooding Dolbadern Castle (1800), the castle where the 13th century prince Owain Goch ap Gruffydd was imprisoned by his brother Llewellyn the Last (so-called, as he was the last prince of an independent Wales before its conquest by Edward I of England) – this was the painting Turner submitted to the RA as his Diploma work, when he was elected, at the youthful age of 27, as a full Academician; Constable’s Boat passing a Lock (1826), The Leaping Horse (1825) as well as a dozen, not so well-known, oil sketches on paper, including the fascinating Cloud Study, Hampstead (1827). It is amusing for us now to reflect that Constable loved the colour green – loathed by Turner and declared abhorrent by the then great arbiter of taste, Sir George Beaumont. There is a famous story of Constable laying a violin on the lawn of Sir George’s house, after the pundit had pronounced that a painting should be the colour of a Cremona violin!

Thomas Gainsborough R.A. – Romantic Landscape – Circa 1783

Oil on canvas 153.70 x 186.70 cms.

Photo credit: Prudence Cuming associates Ltd. © Royal Academy of Arts, London

J.M.W. Turner R.A. – Dulbadern Castle 1800

Oil on Canvas 119.40 x 90.20 cms.

Photo credit: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd.© Royal Academy of Arts, London

John Constable R.A. – The Leaping Horse 1825

Oil on Canvas 142 x 187.30 cms.

Photo credit: John Hammond © Royal Academy of Arts, London.

John Constable R.A. – Cloud Study, Hampstead Tree at Right (11th September 1821)

Oil on paper laid on board, red ground 24.10 x 29.90 cms.

Photo credit: © Royal Academy of Arts, London, photographer John Hammond

One of the most unexpected pieces on display in this room is Turner’s fishing rod – a wood, cane and brass-ferruled ten-piece rod and reel. Turner loved fishing and would often take his rod on his sketching trips. An angling companion wrote of Turner: ‘Turner was as merciful an angler as even the pious and humane father of the craft could have desired. He would impale the devoted worm ‘as tenderly as he loved him’… his success as an angler was great, although with the worst of tackle in the world. Every fish he caught he showed to me, and appealed to me to decide whether the size justified him to keep it for the table; his hesitation was often most touching, and he always gave the prisoner at the bar the benefit of the doubt’.

Room 5 is a small room, with some exquisite watercolours by both Francis Wheatley and Sandby, including his View of Windsor Castle, a panoramic vista of the ramparts and buildings of Windsor Castle, not instantly recognizable as depicted from an unusual angle.

Paul Sandby – Windsor Castle

From the mid 18th century, watercolour played a vital role in the transformation and dissemination of the landscape genre in Britain. The medium was originally adopted for views of historic buildings. Turner worked exclusively as a watercolourist until the age of 21. As a quick-drying and portable medium, watercolour was particularly well suited to travel sketching, and its popularity increased in tandem with the contemporary vogue for touring. From the 1760s onwards, travellers, writers and artists began to seek out areas of special interest in Britain as an alternative to the Grand Tour of the Continent. Picturesque theory identified wilderness and irregularity as important landscape features, thus promoting remote, rugged areas such as north Wales, the Lake District and the Scottish Highlands.

Most visitors would not be familiar with the name of Michael ‘Angelo’ Rooker, ARA (1746-1801, even though he occupies an honourable place among the founders of the British watercolour school for his refined and delicate depictions of ruined castles and monasteries all over England, and enjoyed considerable success in his time. Rooker was trained by both Sandby (who gave him the nickname ‘Michael Angelo’, which stuck) and by his father, Edward Rooker, who was, surprisingly, both an actor and an engraver. Rooker’s paintings and prints combine meticulous topographical accuracy with fleeting atmospheric effects and incidental detail. His watercolour of the imposing 14th century gatehouse of Battle Abbey, exhibited at the RA in 1792, caught the eye of the 17 year-old Turner, who promptly made two studies of it, specifically emulating the technique called ‘colour scaling’, i.e. the depiction of the play of light on crumbling stonework. Turner bought over a dozen of Rooker’s paintings after his death.

Michael ‘Angelo’ Rooker A.R.A. – The Gatehouse of Battle Abbey, Sussex 1792

Pencil and Watercolour on Wove Paper 41.80 x 59.70 cms.

Photo credit: © Royal Academy of Arts,London

So, in short, this is not a monumental or ground-breaking exhibition, but a quietly interesting one, especially for those interested in the genesis and evolution of British landscape painting.

Terence Rodrigues, besides being an author and critic, is an international art consultant, advising private clients on art sales and acquisitions.

He can be contacted on:-

Tel: 07905 474 394 (m) & 0207 828 9255 (w)