This article was commissioned by Robert Jarman for Debrett’s Bicentennial Australia which he compiled and edited 1987. Robert Jarman took great delight in inviting Stewart Aberdour and his wife Amanda to visit Australia during its bicentennial year and to participate in the celebrations of its discovery in 1787 in which his ancestor James Douglas, 14th Earl of Morton, played a major part in funding and organizing.

Lord Aberdour is the son of the present (21st) Earl of Morton whose predecessor, the 14th Earl of Morton, selected James Cook to captain the Endeavour and was directly responsible for the plans to discover the strange land which he was convinced existed in the South Seas or the Pacific Ocean. Lord Aberdour is also a collateral descendant of the famous “Black Douglas” after whom a rather well-known Whiskey is named!

Lord Aberdour writes:-

It is a great pleasure to contribute to the bicentennial celebrations and to record the part played in Australia’s history by my ancestor James Douglas, 14the Earl of Morton.

He was an unusual man. Other bearers of the Black Douglas name had featured in some of the most violent episodes in the stormy history of Scotland, but this Morton was essentially an intellectual; a man of the thesis and the telescope, rather than of blood and the sword.

Yet he lived and held high office in an age of ferment. When he was born in 1702, Edinburgh was still the capital of an independent kingdom. The Union of 1707, by which Scotland and England merged their parliaments and (in theory at least) their national identities, was by no means universally welcomed. Moreover many in ‘North Britain’ and not a few in ‘South Britain’, too, opposed the installation of George I of Hanover, on the British throne. The House of Stuart had a claim: James the ‘Old Pretender’ put it to the test in 1715 and in 1745 his son, Bonnie Prince Charlie’ made another much more serious attempt and very nearly succeeded. His eventual defeat at Culloden, after a succession of brilliant victories, was a catastrophe for his supporters and the bitterness still lingers.

While many in Britain were looking inwards and back, intent on settling old scores and righting wrongs – and no doubt committing new ones in the process – others were looking outwards to the new Worlds across the oceans, and upwards, to the stars.

Morton was one of them, a rue man of the Enlightenment which gave 18th century Edinburgh its reputation as ‘the Athens of the North’. Not that he remained wholly aloof from public affairs: He was one of the 16 peers representing Scotland at Westminster and in 1746, while in Paris, he was arrested and held for three months in the Bastille prison. It is not entirely clear why; but since that was the year of Culloden, and Morton was a noted Whig and supporter of the established order, it may have been at the instigation of French Jacobites.

His main concerns, however, were not political, but; literary and scientific. He had helped to found the Edinburgh Philosophical Society as a young man, and in later life he became a Trustee of the British Museum, a Commissioner in Longitude, and an associate fellow of the French Academy. He was elected to the Royal Society in 1733 and contributed several papers to the Society’s Transactions, mainly on astronomical subjects. In 1764, he became president.

Though not himself in the front rank of scientists, Morton knew almost everyone who was, both in Britain and on the Continent. De Fouchy, chronicler of the French Academy, called him, ‘a true lover of science, and a warm friend of all who adorned it…it may truly be said that no person ever existed who possessed the friendship and esteem of literary men more than he did, and who more deservedly enjoyed the confidence of his government’. That may be though somewhat fulsome; for a British contemporary considered him, ‘of no great Capacity, but for the Ladies: and hath been famous in that Way’!

Whether he was a genuine scholar or merely a well-connected amateur, there can be no doubt that as president of the Royal Society in 1768, Morton was exactly the right man in the right job at the right time. It was an important job, and a crucial time.

Europeans had been exploring the globe, discovering, charting and settling, for many years. But one vast blank still remained: The South Seas of the Pacific Ocean. Was there, or was there not, a Terra Incognita Australis? Physicists had long argued that there must be, somewhere, a great land-mass, as counterweight to the continents of the Northern Hemisphere. How else could the Earth rotate smoothly on its axis? But no-one knew for certain. Did it exist? And if so, was it inhabited – or indeed habitable? There had been hints and scraps of information, but no definitive answers to these last great questions of cosmology. Abel Tasman, from the Netherlands, had found Fiji and Tonga in 1642. He had sighted New Zealand, too, and landed in Tasmania (which he named Van Dieman’s Land after his Governor General). But he had thought those scattered islands of little interest, at least commercially, and the Dutch had turned their attentions elsewhere. Now, the Royal Society was determined to settle the issue. Other nations were in the race, but Britain should be first.

There was another compelling motive. Many years earlier, Edmond Halley (of Comet fame) had predicted that in 1769 the Planet Venus would pass between the Sun and the Earth. Observations of this ‘Transit of Venus’ would provide astronomical information of great value to navigators and cartographers. As a keen student of astronomy and moreover one of His Majesty’s Commissioners in Longitude, Morton was fired with enthusiasm. The transit could be best observed from the South Seas. Why not send an expedition to Tahiti? And, once there, rather than returning home, as so many others had done using the prevailing winds to the north west, why should not this expedition head south, in search of Terra Australis?

He and his colleagues set to work. It was a formidable undertaking. The voyage would be lengthy, perhaps lasting three years, and certainly hazardous. A ship had to be commissioned and equipped; a master and a crew engaged; astronomers and scientists appointed, a mass of scientific records and equipment assembled and installed. Time was short and so – inevitably – was money.

Morton laid his plans, and on February 15 1768, the Society sent George III a memorial which “….Humbly sheweth – That the passage of the Planet Venus over the Disk of the Sun, which will happen on the 3rd of June in the year 1769, is a Phenomenon that must, if the same be accurately observed in proper places, contribute greatly to the improvement of Astronomy on which navigation so much depends….That the like appearance after the 3rd of June 1769 will not happen for more than 100 years….That the British Nation have been justly celebrated in the learned world for their knowledge of Astronomy in which they are inferior to no National upon Earth, ancient or modern; and it would cast dishonour upon them should they neglect to have correct Observations made of this important Phenomenon….” In short, would His Majesty please provide a ship, and £4000?

On March 5th they had their answer. “His Majesty has been graciously pleased to express his Royal inclination…..” to provide both cash and ship.

The next question was, who should command her? in fact the two choices, of vessel and of captain, were interdependent; and there can be little doubt that Morton had already made up his mind about both. though the ship would be a navy vessel, it should not be man-of-war of a frigate. what was needed was a cat-built craft, such as were employed in the coast trade. Yet she must be commanded by a naval officer, the Admiralty were adamant on that point. They had tried placing naval personnel under civilian command once before, with Halley, and the result had been mutiny and near disaster. So what was needed was a navy captain who knew about handling coal vessels, an officer who could maintain discipline, while co-existing amicably with the scientific gentlemen, a highly skilled navigator, bold but prudent, a man of action, but of scholarly sympathies. A tall order indeed, but as it happened Morton knew just the man.

Two years earlier he had been astonished to receive, as president, a detailed report on an eclipse of the sun observed off Newfoundland. It was an excellent report, but its most surprising feature was that it was written by a man of little education, the son of a migrant farm-worker, who had worked on coasters since his boyhood, transferred to the navy as an able-seaman at the age of 27 but had still not , at 38, attained commissioned rank. To the Society’s credit, his report was accepted and published. It was the work of one J. Cook, “a good mathematician and very expert in his business”.

There were other candidates for the command of the Endeavour, but Morton wanted J. Cook. He could not have chosen better. James Cook must surely rank as one of the finest all-round navigators – if not the finest – the world has ever known. He had already done excellent work in the North Atlantic, but his achievements in the Pacific and the Antarctic were to become legend, and his ‘Journals’ are classics in their own right. A man of iron self-control, but bold when required, he had the respect of all who sailed with him. His seamanship was almost uncanny. Sailors swore that he could ‘smell’ land and he certainly made some amazing landfalls across uncharted waters. He was unusually humane as a disciplinarian though no less effective for that, and keenly interested in hygiene and diet. His particular concern was to combat scurvy, which regularly decimated ships’ companies on long voyages. Here, too, he succeeded. On Endeavour there was not one death from scurvy in three years.

Morton had his way. Cook was hastily commissioned lieutenant – a rank he might otherwise never have achieved – and given the command of Endeavour. naturally she was a cat-built vessel, such as were employed in the coal trade; just the sort of craft Cook had sailed for most of his life.

It is sobering, now, to reflect on how small she was for such a stupendous voyage. Less than 400 tons displacement, she was scarcely a hundred feet long and ‘cat-built’, broad at the waist, to accommodate the mass of stores and scientific supplies. The Society selected their representatives: Joseph banks, botanist and leader, with Daniel Solander as associate; Alexander Buchan and Sydney Parkinson, artists; Charles Greene, astronomer; and numerous assistants. Clearly, a second astronomer was necessary to make such important observations. Yet the passenger list was already very long. Why not, Morton suggested, J. Cook himself? It was a brilliant idea, and a generous one – the fee of 100 guineas was a welcome supplement to his naval lieutenant’s pay of five shillings a day.

The ship was refurbished by the Admiralty, but the scientific apparatus was for the account of the Society. It is not known how much Morton contributed, but Banks – who later became president to the Society – is believed to have spent no less than £10,000, a vast sum in those days.

The navy appointed the crew though Cook approved most of the key personnel. He was frustrated in just one choice, that of the ship’s cook. The Admiralty’s first nominee was a cripple, clearly unsuitable, and he was withdrawn after strenuous protests. But the second nomination stood, despite renewed protests, although the man in question, John Thompson, had only one hand! All was well, as it happened – Thompson proved to be a very fine cook indeed and no complaint was ever lodged about the food on the Endeavour throughout the three years of the voyage – which must surely be unique in the annals of the Royal navy, or any other navy for that matter.

When at last all was ready, Moron compiled, “Hints offered to the consideration of Captain Cooke, Mr. Bankes, Doctor Solander, and the other gentlemen who go upon the Expedition on Board the Endeavour”. It seems to me a remarkable document, full of curious knowledge and common sense, and I only wish there were space to quote it in full. (The original is housed, most appropriately, in the Commonwealth National Library in Canberra.) Morton comments on virtually every aspect of the expedition’s goals but contrives to do so without a trace of arrogance. There is no hint of condescension, of the patron patronising his protégé which Cook undoubtedly was. It is all couched in terms of modest, friendly interest and concern, as from one student of the sciences to his brother scientists. It reads extremely well.

Let me cite just one passage. Morton clearly believed that there was a Terra Australis, and that it was probably inhabited. There had been many brutal encounters between Europeans and indigenous peoples, and he was anxious that the Royal Society should not be the instigators of yet more. So how should the crew of the Endeavour behave?

He counselled them: “To exercise the utmost patience and forbearance with respect to the Natives of the several Lands where the Ship may touch. To check the petulance of the Sailors, and restrain the wanton use of Fire Arms. To have it still in view that shedding the blood of those people is a crime of the highest nature. They are human creatures, the work of the same omnipotent Author, equally under his care with the most polished European, perhaps being less offensive, more entitled to his favour. They are the natural, and in the strictest sense of the word, the legal possessors of the several Regions they inhabit. No European Nation has a right to occupy any part of their country, or settle among them without their voluntary consent. Conquest over such people can give no just title: because they could never be the aggressors…”

One wonders what the world would be like today, had geopolitical affairs only been conducted over the last two centuries on ‘Mortonian’ principles.

In August 1768, the Endeavour set sail; and the rest is history. The Transit of Venus was duly observed and recorded, and then Cook headed South. Many islands were discovered and charted, and New Zealand was circumnavigated for the first time. And Terra Australis was there. On April 19th , 1770, the Endeavour passed Point Hicks, and on April 29th the expedition landed at Botany Bay. (The name records the delight of Banks and Solander at the richness of the vegetation for their study.) Then came the long haul north along the whole Eastern seaboard, the passage of the Great Barrier Reef (a perilous undertaking even with modern craft), and the final pull via Djakarta and the Cape to England, in triumph, on June 12, 1771.

Morton did not share that triumph. Worn out by his exertions, he had died on October 12, 1768, only weeks after the Endeavour set sail.

But James Cook had not forgotten his “friends in high places”. He named the “Society” Islands in August 1769, and his Journal for May 17, 1770, records: “On the north side of this point the shore forms a wide open bay which I named Morton’s Bay….This land I named Cape Morton, it being the North point of the Bay of the same Name.” (Cook himself wrote “Morton”, and the “e” seems to have been inserted by the first transcriber of his text. But no great matter, eighteenth-century spelling was variable and Morton himself had addressed his Hints to “Captain Cooke

Mr. Bankes” and the others.) Anyway, there they still are: Moreton bay and Moreton Island and Cape Moreton. Far sighted though he was, he could hardly have imagined the development of the great city of Brisbane. But had he done so, I like to think that he would have been proud that he had helped, in some measure, to make it all possible. His descendants are.

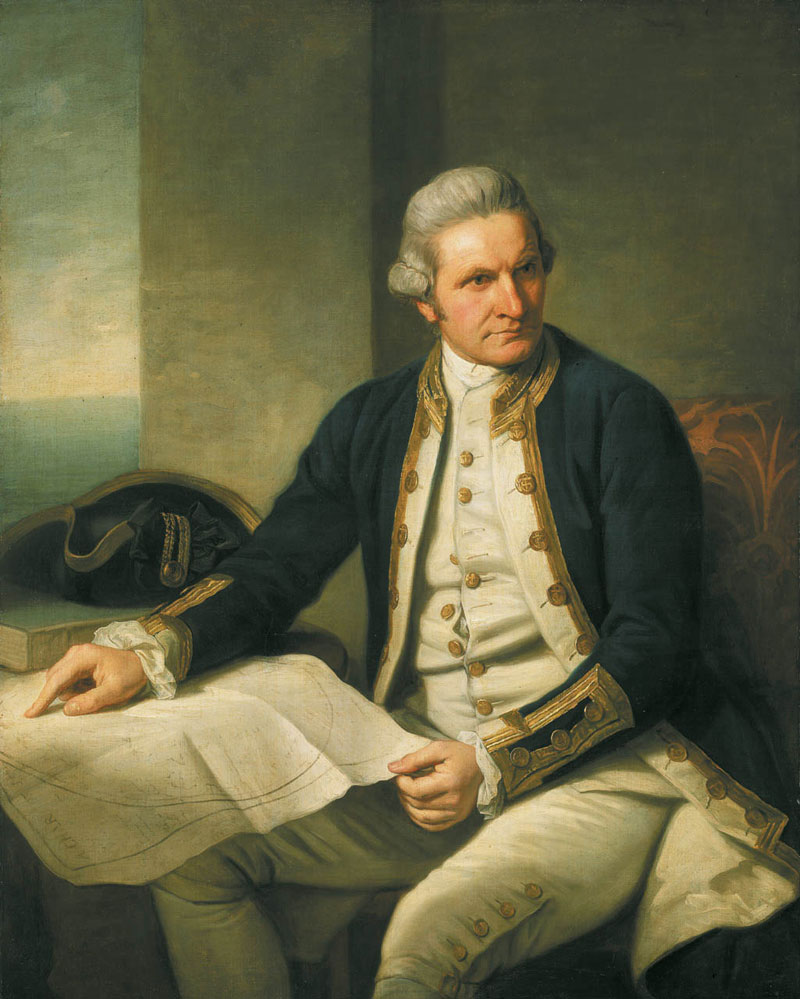

PORTRAIT OF CAPTAIN JAMES COOK BY NATHANIEL DANCE

A three-quarter-length portrait of Captain Cook, seated to the left, facing the right. He is wearing captain’s full-dress uniform, 1774-87, consisting of a navy blue jacket, white waistcoat with gold braid and gold buttons and white breeches. He wears a grey wig or his own hair powdered. He holds his own chart of the Southern Ocean on the table and his right hand points to the east coast of Australia on it. His left thumb and finger lightly hold the other edge of the chart over his knee. His hat sits on the table behind him to the left on top of a substantial book, perhaps his journal, itself resting on the chart. In 1772, Cook sailed for the second time to the fringes of the Antarctic and the Pacific, returning in 1775. He sat for this portrait, commissioned by Sir Joseph Banks, ‘for a few hours before dinner’ on 25 May 1776 but it is not known whether he did so again before he left London on 24 June for his third voyage, never to return. None the less, David Samwell, surgeon’s mate in ‘Resolution’ on the second voyage and surgeon of ‘Discovery’ on the third, thought it ‘a most excellent likeness … and … the only one I have seen that bears any resemblance to him’. This view was based on John Sherwin’s later engraving of the portrait, which probably argues even more favourably for the original despite an element of idealization, not least omission of a large burn scar (from 1764) on the right hand. Banks had sailed with Cook on his first voyage in the ‘Endeavour’ and took an influential interest in his subsequent ones. This portrait hung over the fireplace in the library of his London house. After his death, it was presented to the Naval Gallery at Greenwich Hospital by his executor, Sir Edward Knatchbull, following a request by E.H. Locker, the Hospital Secretary In 1781-83 Charles Grignon, then in Rome, painted a ‘Death of Captain Cook’ which was sold in 1821 after the British Museum declined it as a bequest from his brother Thomas, a well-known watchmaker. That picture subsequently disappeared but Thomas’s will says the likeness of Cook was based on the present portrait. Dance worked with Pompeo Batoni in Rome and on his return to London in 1765 achieved success as a portrait and history painter. In 1768, he joined a group of artists who successfully petitioned George III to establish the Royal Academy in that year.

This portrait hangs in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Greenwich Hospital Collection.